Homo Economicus

A Homo Economicus is an person model that is rational self-interested agent who usually pursue their subjectively-defined ends optimally.

- AKA: Economic Human.

- …

- Example(s):

- …

- Counter-Example(s):

- See: Production (Economics), Cooperation#In Humans, Economics, Economic Theories, Rationality, Rational Egoism, Agency (Philosophy), Optimal Decision, Utility Maximization Problem, Consumption (Economics), Economic Profit, Behavioral Economics.

References

2020

- (Wikipedia, 2020) ⇒ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/homo_economicus Retrieved:2020-10-4.

- The term homo economicus, or economic man, is the portrayal of humans as agents who are consistently rational, narrowly self-interested, and who pursue their subjectively-defined ends optimally. It is a word play on Homo sapiens, used in some economic theories and in pedagogy. In game theory, homo economicus is often modelled through the assumption of perfect rationality. It assumes that agents always act in a way that maximize utility as a consumer and profit as a producer, and are capable of arbitrarily complex deductions towards that end. They will always be capable of thinking through all possible outcomes and choosing that course of action which will result in the best possible result.

The rationality implied in homo economicus does not restrict what sort of preferences are admissible. Only naïve applications of the homo economicus model assume that agents know what is best for their long-term physical and mental health. For example, an agent's utility function could be linked to the perceived utility of other agents (such as one's husband or children), making homo economicus compatible with other models such as homo reciprocans, which emphasizes human cooperation.

As a theory on human conduct, it contrasts to the concepts of behavioral economics, which examines cognitive biases and other irrationalities, and to bounded rationality, which assumes that practical elements such as cognitive and time limitations restrict the rationality of agents.

- The term homo economicus, or economic man, is the portrayal of humans as agents who are consistently rational, narrowly self-interested, and who pursue their subjectively-defined ends optimally. It is a word play on Homo sapiens, used in some economic theories and in pedagogy. In game theory, homo economicus is often modelled through the assumption of perfect rationality. It assumes that agents always act in a way that maximize utility as a consumer and profit as a producer, and are capable of arbitrarily complex deductions towards that end. They will always be capable of thinking through all possible outcomes and choosing that course of action which will result in the best possible result.

2018

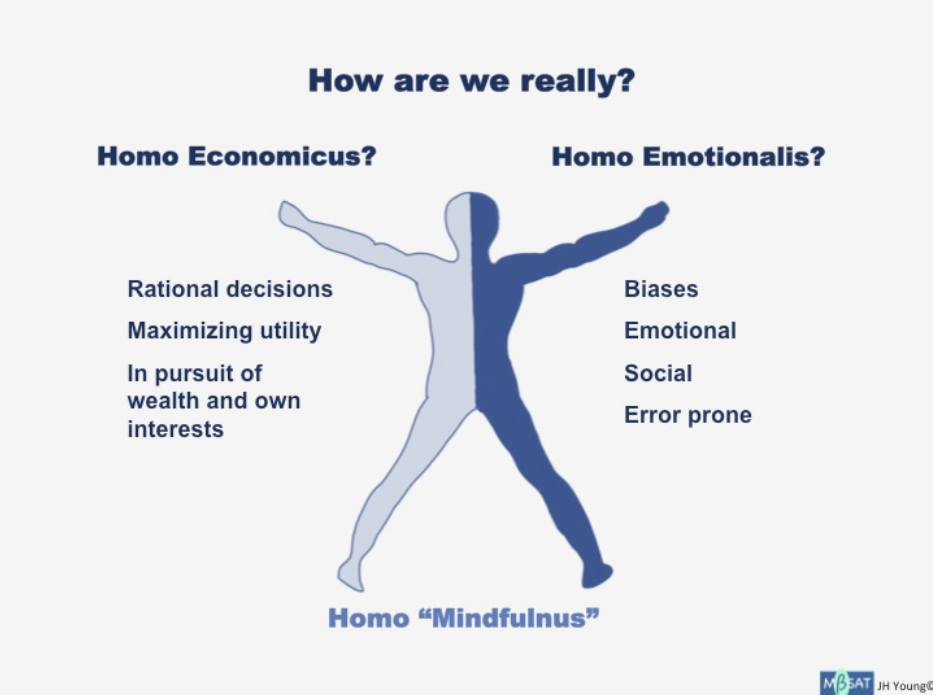

- https://www.juanhumbertoyoung.com/2018/03/29/homo-economicus-homo-emotionalis-toward-homo-mindfulnus/

- QUOTE: ... The contemporary view of Homo economicus originated when amongst others some UChicago economists merged these two postulates to create theories suggesting that people base their life decisions on a rational pursuit of value that leads to maximizing their utilities (happiness, wealth, and any other desirable good). Given the zero-sum effects (one’s gains come mostly from someone’s losses) of these theories this implies the assumption that individuals must act selfishly to have any hope of realizing their aspirations. ...

- QUOTE: ... The contemporary view of Homo economicus originated when amongst others some UChicago economists merged these two postulates to create theories suggesting that people base their life decisions on a rational pursuit of value that leads to maximizing their utilities (happiness, wealth, and any other desirable good). Given the zero-sum effects (one’s gains come mostly from someone’s losses) of these theories this implies the assumption that individuals must act selfishly to have any hope of realizing their aspirations. ...

2001

- (Henrich et al., 2001) ⇒ Joseph Henrich, Robert Boyd, Samuel Bowles, Colin Camerer, Ernst Fehr, Herbert Gintis, and Richard McElreath. (2001). “In Search of Homo Economicus: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-scale Societies.” American Economic Review, 91(2).

- QUOTE: ... Recent investigations have uncovered large, consistent deviations from the predictions of the textbook representation of Homo economicus (Alvin E. Roth et al., 1991; Ernst Fehr and Simon Gachter, 2000; Colin Camerer, 2001). One problem appears to lie in economists' canonical assumption that individuals are entirely self-interested: in addition to their own material payoffs, many experimental subjects appear to care about fairness and reciprocity, are willing to change the distribution of material outcomes at personal cost, and are willing to reward those who act in a cooperative manner while punishing those who do not even when these actions are costly to the individual. These deviations from what we will term the canonical model have important consequences for a wide range of economic phenomena, including the optimal design of institutions and contracts, the allocation of property rights, the conditions for successful collective action, the analysis of incomplete contracts, and the persistence of noncompetitive wage premia. …

1776

- (Smith, 1776) ⇒ Adam Smith. (1776). “An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...."

- QUOTE: ... As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. …