Chinese National Debt to GDP Ratio

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

A Chinese National Debt to GDP Ratio is a national debt-to-GDP Ratio for a Chinese economy (based on Chinese national debt and Chinese GDP).

- Context:

- It can range from being a Chinese Public Debt to GDP Ratio to being a Chinese Private Debt to GDP Ratio.

- …

- Example(s):

- Counter-Example(s):

- See: Chinese National Government, Chinese Labor Participation Rate.

References

2019

- (Wikipedia, 2019) ⇒ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_debt_of_China#Size Retrieved:2019-2-18.

- The International Monetary Fund, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [1] and other sources, such as the Article IV Consultation Reports,[2] [3] state that, at the end of 2014, the "general government gross debt"-to-GDP ratio for China was 41.54 percent.[4] With China's 2014 GDP being 10,356.508 billion, [5] this makes the government debt of China approximately 4.3 trillion.

The foreign debt of China, by June 2015, stood at around 1.68 trillion, according to data from the country's State Administration of Foreign Exchange as quoted by the State Council.[6] The figure excludes the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau. Chinese foreign debt denominated in the U.S. dollar was 80 percent of the total, euros 6 percent, and Japanese yen 4 percent.

- The International Monetary Fund, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [1] and other sources, such as the Article IV Consultation Reports,[2] [3] state that, at the end of 2014, the "general government gross debt"-to-GDP ratio for China was 41.54 percent.[4] With China's 2014 GDP being 10,356.508 billion, [5] this makes the government debt of China approximately 4.3 trillion.

- ↑ "General government gross debt for China", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- ↑ "People's Republic of China 2015 Article IV Consultation - Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for the PRC" IMF Country Report No. 15/234

- ↑ An "Article IV consultation" is a "regular, usually annual, comprehensive discussion" between IMF staff and representatives of individual member-countries concerning the member's economic and financial policies, conducted on the basis of Article IV of the IMF Articles of Agreement. See: IMF Glossary

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database, October 2015, IMF

- ↑ China, World Bank

- ↑ "China's external debt stands at $1.68 trillion in June", State Council announcement, 2 October 2015

2020

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/270329/national-debt-of-china-in-relation-to-gross-domestic-product-gdp/

- QUOTE:

Find more statistics at Statista

- QUOTE:

2016

- The Economist. (2016). “It is a question of when, not if, real trouble will hit in China.” In: The Economist, May 7th 2016

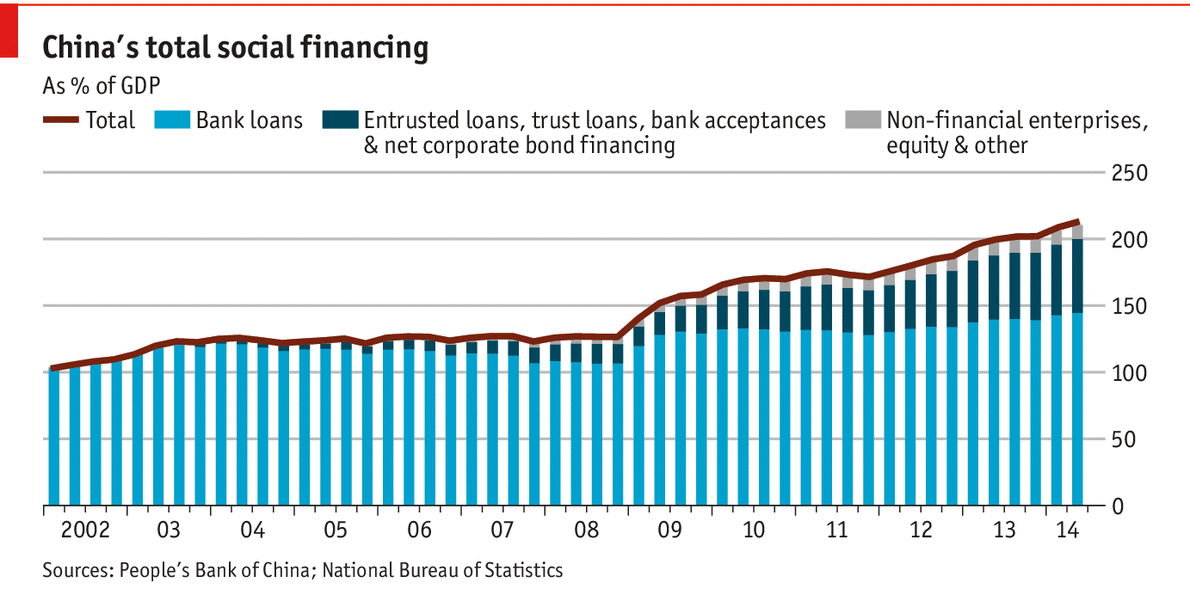

- QUOTE: CHINA was right to turn on the credit taps to prop up growth after the global financial crisis. It was wrong not to turn them off again. The country’s debt has increased just as quickly over the past two years as in the two years after the 2008 crunch. Its debt-to-GDP ratio has soared from 150% to nearly 260% over a decade, the kind of surge that is usually followed by a financial bust or an abrupt slowdown. China will not be an exception to that rule. Problem loans have doubled in two years and, officially, are already 5.5% of banks’ total lending. The reality is grimmer. Roughly two-fifths of new debt is swallowed by interest on existing loans; in 2014, 16% of the 1,000 biggest Chinese firms owed more in interest than they earned before tax. China requires more and more credit to generate less and less growth: it now takes nearly four yuan of new borrowing to generate one yuan of additional GDP, up from just over one yuan of credit before the financial crisis. With the government’s connivance, debt levels can probably keep climbing for a while, perhaps even for a few more years. But not for ever.

2015

- The Economist

- QUOTE:

- QUOTE: